Sun 19 Jul 2015

In the footprints of ymps

Posted by PJ under england 2004, folklore, madron, magic

No Comments

Back in 2004, two friends and I visited the Cornish peninsula. Tintagel was definitely a high point—the actual rock and castle itself, if not the village. But there was another place that left just as big an imprint on my soul—maybe even bigger. Not as dramatic as Tintagel, much quieter, but no less magic: St. Madron’s Holy Well in Cornwall.

It’s inland from Penzance only a few miles, but a whole different world from the bustling tourist centers along the coast. It wasn’t featured prominently in my Green Guide, but I’d read about the well elsewhere and it figured high on my wish list. My companions indulged me in this, and I think they were glad they did. We were an Episcopalian, an agnostic, one leaning strongly towards pagan, and all of us were all moved by this place. It’s been holy since pagan times, taken over by the Christians, and still remains holy to both. There are a couple of small churches nearby, St. Madron’s which we didn’t get to visit, and St. Grada—small, lovely, peaceful. But the well itself (and the ruined chapel channeling it) exist a mile north and a whole ‘nother universe apart.

It’s a half-mile, so they say, from the church to the gate leading to the well, and a quarter mile in to the ruined chapel. Pastures surround the location, and the gate opens onto a tree-lined path. On this spring day, the trees burned with blossoms. We progressed through dappled shade along the rough path, delicate wildflowers in white and pink and yellow leading the way. Maybe it’s the screen of trees that shuts off all noise except the chirping of birds, the occasional movement of wild things in the overgrown brush on either side, but it’s like stepping into another world, so different from the one we know—centuries older, maybe a millennium or two. We hushed in response, the sound of our quiet passage seeming unnaturally loud. We could hear the wheels of our own thoughts spinning in our heads.

It hadn’t rained for several days, but the path was still damp, quite muddy in spots, sunken beneath water in places. Sometimes we had to scramble over rough stiles, crudely cut blocks of gray stone. One to step up, a flat one to scramble over, one to step down.

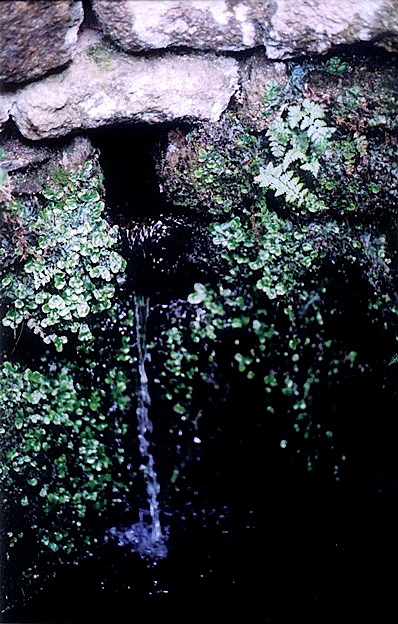

The waters of the wellspring, I learned later, is somewhere out in the marshy land beyond the chapel, but they say its water brings healing and also gives mystical insight into the future. Puritan fanatics tried to smash the well housing in the chapel during the Civil War, but it still burbles on with fresh, pure, clean water. We were there on a Saturday, the end of April, but the waters are supposed to be their most potent on the first three Sundays in May. Maybe we got some residual from the build up to May, who knows?

After the second stile and down a bit, there’s a stand of trees where people who’ve been cured by the well leave an offering—traditionally rags tied to the trees, but we saw all sorts of things. We left our offerings before the fact. All I had on me was a crimson velveteen scrunchie for my hair, one I was particularly partial to. I must say it looked lovely wrapped around the broken end of a branch.

A real presence exists in that place, a sense that something potent moves through those trees. I didn’t feel at all silly looking back on that crimson scrunchie. It felt damned good, an elevation of the spirits. No guarantees of anything, no promises made, but for me a sense that I was making a wordless promise; I gave up something to the spirit of the place.

I’m not exactly sure why that particular bend in the stream became the location of the rag offerings because it’s around the path and down a ways from the actual well site. But I do know that the stream forked at this point, and in pagan beliefs, at any rate, forks in rivers are magical places. As are forked trees—ymp trees, they’re called, where the branches split in a Y low enough on the trunk for a human to walk or climb through easily. There were some of those in that grove, too. Forks represent transition points, places where the energy (or magic) changes directions and, some believe, gives a surge of power.

The chapel itself is a ruin, a roofless box of ancient stone, steeped in age and covered in moss. An altar, on this day hosting a crude cross woven of branches, sits at one end of the enclosure.

The interior housing for the well is another, smaller box on the opposite side, with a catch basin for the waters before they flow out and into the stream. A cold, absolutely clear, surprisingly gentle stream for such a volume of water—and again, the sense of presence was palpable. Even if you don’t go in for the mystical stuff, the thought that for thousands of years humans have come to this spot for prayer and offerings is awe-inspiring. Maybe that’s all the presence is at Madron, those innumerable human lives and energies intersecting with this place. Whatever it is, it’s potent. We sat on the rough stones for longest time, drinking it in, letting the peace invade our souls and smooth out the jangles. I was healed, although I hadn’t been aware of being sick.

I snapped a few pictures, but it seemed a futile (and maybe sacrilegious?) endeavor, and none of them came out all that well. I couldn’t escape the realization that no film, no picture could capture the enveloping green peace of this place, surrounded by trees, accompanied by the trill of songbirds, the plash of water on stones, the gurgle of it running in a channel, the fresh smell of greenness all around. At best, these photos may jog memories years hence, opening the door to the soul memory left behind by St. Madron’s Well.

No Responses to “ In the footprints of ymps ”