Mon 2 Oct 2023

All Weird Things, Episode 5 – The Faces of Strangers

Posted by PJ under ability, all weird things, brain, mind, necromancy, perception, synesthesia, thinking

No Comments

For as far back as I can remember whenever I’ve closed my eyes in preparation to sleep the faces of strangers appear in my mind’s eye—like on the cinema screen behind my eyelids. They stare down into my face, quite close. Sometimes they back off and I see details of their clothing—from many different eras, but mostly the 20th and 21st centuries. (As I write this the vivid memory of a blonde curly haired girl in a red fifties-style flare dress with large white polka dots comes to mind. Her hair was just above her shoulders, and she wore a white headband. She looked to be in her twenties.)

These people almost always have serious or concentrated expressions. I can’t recall an instance of them smiling, though sometimes they just have a curious neutrality. It’s as if they want something from me but I never know what. Maybe just to give them a spot of attention? They know, I’m convinced, that I see them with my eyes closed but not with my eyes open and want to get that attention while they can, though sometimes they seem genuinely surprised to be perceived. They never stay long, and I rarely feel anything menacing, just their passing flare of interest before they move on. These are people I’ve never seen before in my life or since. It isn’t a nightly occurrence, but a fairly frequent one.

I used to think this happened to everyone. Diana Gabaldon even talked about it in one of her Outlander novels. But when in my latter years I mentioned it to friends—“You know that thing where sometimes when you close your eyes you see the faces of strangers?”—they were incredulous. “No,” they said, “that’s never happened to me.”

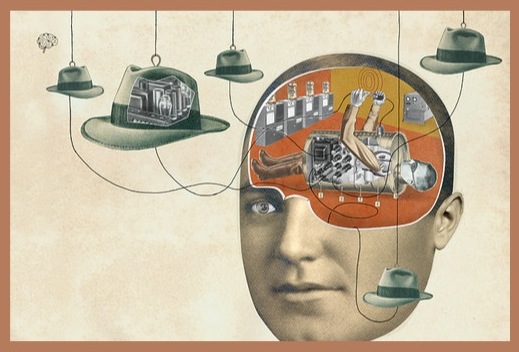

So I realized that my eyelid friends were one of those things—like styles of thinking—that we assume are universal, a part of everyone’s experience, because we only live inside our own heads and can’t know how others perceive the world. I didn’t learn until fairly recently, for instance, that not everyone has a constant running monologue in their head. I started seeing articles about it. I was dumbfounded. It made me think of my friend who has synesthesia. She didn’t realize when she was little that not everyone had specific colors attached to each letter in the alphabet or that sometimes words had a vague flavor to them. The chatterbox in my mind doesn’t drive me crazy because I’m used to this state of being but it is always narrating. (Okay, yeah, when I’m in a worry cycle it does drive me crazy, but I’ve developed coping mechanisms.) (And yes, my synesthesia friend also has a running monologue in her head.)

So I wasn’t worried about all those strangers clamoring for my attention. I didn’t know any better for most of my life and once I knew it wasn’t that way for everyone I was curious as to what it was but still not alarmed. I did wonder if it was some weird way of seeing spirits of the dead but didn’t really pursue that. Until I mentioned it to a witch acquaintance I had at the time (we’re no longer in communication) who practiced necromancy.

“Transient spirits,” she said. “They are attracted to you because they know you can see them, but you have to be careful. They can suck your energy, make you sick, and do other harm if you don’t protect yourself.”

For the first time in my life I became uneasy with them. She was a necromancer so she had to know more about this than I, right? Forget the fact I’d never perceived harm from these folks, I took this unsolicited advice to heart. From that point on whenever the strangers showed up I’d say, “You’re not welcome here. Go away.” Poof! They were gone. Their visits got less and less frequent then stopped altogether. But the funny thing was I missed them. I felt bereft of these “companions,” as if something essential had been taken from me. Worse, that I’d taken it from myself on the advice of someone who was just guessing.

I started saying to the Great Whatever, “I welcome all spirits who mean me no harm,” but the damage had been done. They didn’t return. And, of course, I don’t really know if they were spirits at all. They could have been an aspect of my active imagination and I’ve wondered since if that’s a component in why I sometimes struggle more with my creative work then I used to.

I want them back, those strange transient companions. It’s not the only time I have forcefully shut down an “ability” because I got uncomfortable, but that’s a story for another day. Today I’ll just say that the mind is a curious enclosure and we all live in an illusion of the world to one degree or another. We can only perceive the world as our minds allow us and can never truly participate in the thought processes of anyone else. Perception is a closed circle—or more precisely, perhaps, a labyrinth in which we wander endlessly.