Tue 6 Jul 2021

Things I learned about light

Posted by PJ under despair, illusion, memories, photography

No Comments

I was once a prodigious photographer. For about 20 years back in the mid-70s to mid-90s I never went anywhere without my camera. First a Minox 35 GL then a Canon AE-1. I loved the little Minox, but it was automatic focus, you see, and I wanted more control. So I got the Canon. I couldn’t afford a Nikon at the time, but the Canon was highly rated and I was happy with it. I experimented with a lot of things—infrared film, timed exposures, B&W portraits, etc., etc. I used film, I used slide film. Back then I could talk the talk, but like any skill long out of practice, I’ve forgotten much of it. But I was left with a mountain of film strips and slide boxes.

Once I switched to digital, first with a baby Nikon, then the lazy way with my cell phones, I became a snapper rather than a photographer. This may have been because with my old manual camera I had to stop and consider each shot. Frame it, decide what f-stop to try, experiment with focus, etc. This was true even of the Minox. The focus was automatic, but I was still responsible for the light settings, et al.

Or maybe I always took a bunch of crappy photos and once a roll or so got lucky. Maybe I was just pretending to be a photographer and was nothing but a delusion dilettante, a snapper, a poseur. (You know the Imposter Syndrome drill.)

But at least with digital I didn’t have to worry about mountains of film strips and slides. And I had ceased being a serious photographic aficionado at some point, mainly (maybe) due to the cost of buying and developing film, maybe for other reasons I no longer remember or want to admit. Photography back in the olden days was not an egalitarian pursuit. It cost money, and not just the initial expense for nice cameras. It was a money pit of film and developing and dark room supplies. (I did get marginally smarter at a certain point and started getting proof sheets rather than paying for everything to be developed, but still.) At least with good digital and good camera phones available many more people can pursue this art form.

I got an expensive high-quality flatbed scanner back in ’06 or thereabouts and started digitizing things. But scanning is a laborious process and I was not dedicated to getting through that mountain of film stuffs quickly. After a while, the scanner went belly up. I tried reloading the software and doing a bunch of other things but alas. It may have been a victim of a power surge, but I didn’t have the ambition to send it to the dealer so I’ll never know. The warranty had run out and I didn’t want to spend the money, frankly. Recently, I thought I really should do something about that film mountain so back in April I acquired a cheaper but still well-rated mini scanner and began the process again.

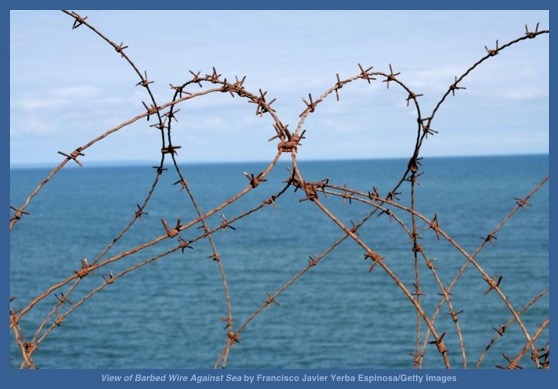

At first it was a giant surprise seeing what came up on the screen, a half-remembered country that had once been so important to me. But I quickly discovered (actually, I knew this but didn’t want to acknowledge the fact) that the quality of both film and slides degrade badly over time. I also discovered what an awful lot of really bad photos I had taken. True, I started scanning with a set of vacation slides I’d taken in the early 80s in Seattle and they may not have been representative of my overall skill. In my mind, though, I remembered getting some great stuff. And if I can ever find the prints I had made of those slides back then, maybe I did or maybe I didn’t. Particularly disappointing were the pix I took of Puget Sound with its heart-stopping green beauty. I remember being pleased with how they came out—even though no photo could really capture the totality of that beauty. But when the scans came up on the screen, everything was washed out or too dark and even photoshopping couldn’t redeem them. It was so discouraging I quit scanning in despair, feeling like an entire portion of my life had been nothing but a sham.

Yesterday, I chided myself into doing more scanning. “Either scan this stuff or throw it out.â€* There was one picture in particular I wanted to find but who knew where the hell it was, which box or envelope. I had labeled many of them, but not all. I picked some unlabeled slide boxes at random, opened the first one, and there it was, right on top. And it hadn’t degraded!

Not a startlingly great shot but one I remembered fondly. One of those once in a roll lucky shots. One that let me know that I may have been mostly crap, but every once in a while I was slightly less crap. (Kind of like the old proverb, “Even a blind squirrel gets a nut once in a while.â€)

I’m still looking for other remembered pictures, that lost horde of imagined gold, hoping the slides haven’t degraded too badly. Certain signature shots that loom large in my mind. They may turn out to be just as disappointing as those Seattle snaps, but one lives in hope.

*Please note: I have thrown away some of the crappy stuff, but find myself completely incapable of throwing out even the crappiest shots of any animal I have ever known and loved.